... But join the corners using the most bombproof joinery available: through-dovetails.

A lot is written about dovetails because they appeal to a type of modern aesthetic yearning for a hand-built object. Dovetails have come to symbolize aspects of the hand-tool woodworking ethos. However, this is doing dovetails a disservice because they are not just a pretty joint (in the past they were often hidden), they are not art, but a fundamental method for furniture work.

Dovetails are anything but fancy. The dovetail is a hard-working joint that keeps your chests, closets, and bookshelves from falling apart. The dovetail is a dependable joint that will wear down the years while still holding tight. The dovetail should be cut so often that it becomes second-nature. The dovetail should become, if you'll pardon my language, gosh-darn quotidian.

This article is a review of how I've been cutting dovetails in maple as I went about building four sets of maple bookshelves for the home. I am not suggesting that this technique is better than any other, but merely recording the technique which I ended up using on this wood and for this project.

I cut tails-first because that is what I'm used to, but the photo series in this article shows cutting the pins. Despite the basic approach being same for both tails and pins, when working tails-first the pins cut is the more intricate and interesting.

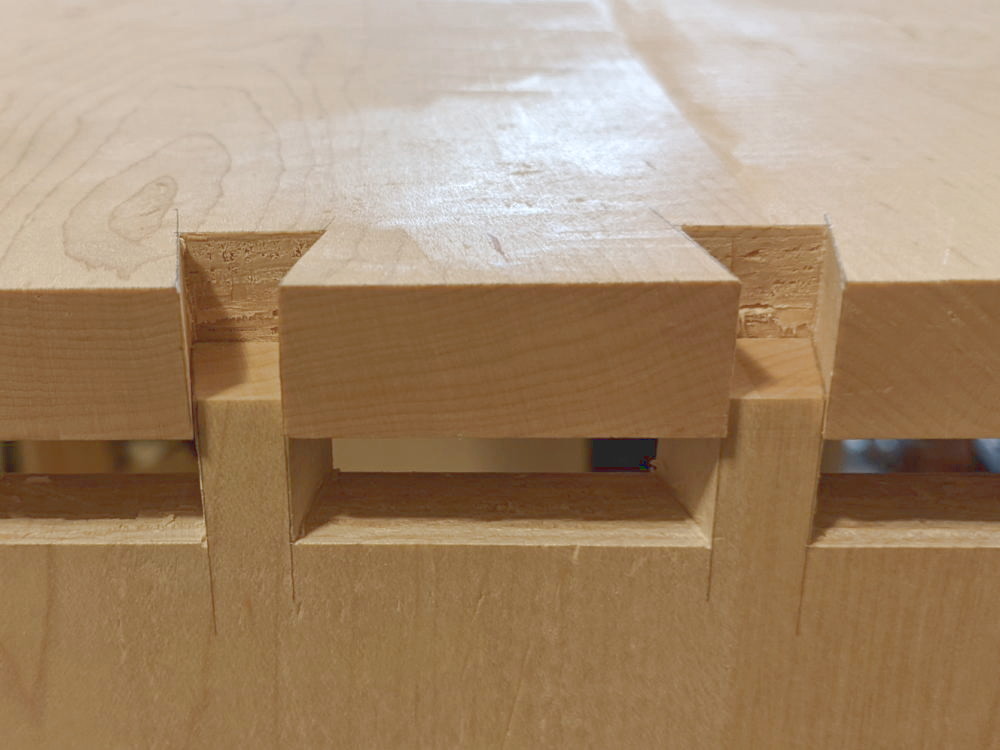

The bookshelves are 12" deep, so I divided them into 5 tails, each with a base of 1¾", and a slope of 1-in-7. I choose an odd number of tails because I like the look of dovetail in the center. As for the rest, I flipped through photographs and drawings in several of my woodworking books to decide on the slope and width that pleases my eye. No serious engineering considerations were taken to determine these numbers, outside of making sure that the pins at the ends are wide enough not to break off.

I always mark the waste before cutting. Distracted Woodworking is a real threat, faced by many woodworkers every day. Clearly marking which part goes to the fire and which stays as furniture is a good way to avoid serious sawing sorrow.

I'm using Western-style saws (cut on push), so I cut from the show-face of the piece. Therefore, I only mark cutting lines on the show-face of the piece. I mark the pins by overlaying the tails, so I don't care where the lines on the other side appear, nor do I care about how they look. My primary care when cutting the tails is to keep my saw vertical. Similarly, when I cut the pins I do the same, but I also need to cleave to the scribed lines.

I mark the baseline on the face side using a cutting gauge. I then slide a chisel at a 45° angle along that baseline. This creates a beveled slope down to the cut baseline. The procedure is straightforward but delicate, especially when working on the show-face.

The result is a relief against which I can securely place a chisel. In other projects I've cut the same slope by chiseling down to the cut baseline with light taps of a mallet, but I found this sliding method to be effective and consistent when working with hard maple. One of the main goals is to leave a crisp and straight baseline, so I start gently with the chisel.

The process now flips between tapping the chisel down with its back against the baseline, and gently splitting off some wood down to that baseline. When half of the waste has been split away I flip the board over and work from the other side.

Attention needs to be given to the direction the wood splits. If the grain is diving down into the board, and the baseline cut isn't deep enough, then you will be trying to split the entire board in half. I avoid this by making numerous small splits instead trying to take big bites. There is a moral in there somewhere.

The process is only subtly different from the often taught method of chiseling down to the baseline at an angle. This instead is a way of exploiting the wood's natural weakness in splitting it directly down the grain.

You probably won't want to try this with a soft pine or poplar, as those may split too easily. With hard maple, however, any opportunity to work with less force is welcomed. The technique also measures favorably with others in terms of how long it takes. All good hand-tool techniques eventually become fast with enough repetition.

I learned two things from this process. First, it is valuable to modify my techniques to account for the material at hand. There is something to be said for studying the gold standard and then doing something else. Second, immersing myself in large-scale projects gives me the time and practice to develop those variations. It would be hard to come to a conclusion regarding any new technique if I only had a handful of dovetails to cut.